2024 Bethesda Visitors Guide

Welcome to Bethesda! Bethesda, Maryland is a thriving unincorporated urban district in the Washington, DC Metro Area that is bursting with shops, restaurants, theaters, and art galleries. Bethesda’s most famous attraction is the sheer diversity of its restaurant scene, with numerous dining spots that beckon invitingly from well-maintained storefronts along quaint tree-lined streets.

Things to do in Bethesda MD

Located just minutes away from Washington, D.C., this urbanized and extremely wealthy community is home to the National Institute of Health, Lockheed Martin Corporation, and a sizeable portion of the greater capital area’s six-figure income employees. Bethesda is lacking in vibrant nightlife but offers an ample amount of shopping, art galleries, and performance venues – both in town and in neighboring communities – to keep any visitor busy. Downtown Bethesda is particularly famous for its dining scene is considered to have some of the best restaurants in the region and can be a pleasant place to amble along the sidewalks. But if you find yourself itching to explore a more lively area, public transportation offers easy access to Washington, D.C.

Audubon Naturalist Society – Woodend Sanctuary

8940 Jones Mill Road, Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815; Tel. 301.652.9188

It might come as a surprise that the nation’s capital is just a stone’s throw away from a wealth of opportunities to explore nature. One of the best is the Woodend Sanctuary in nearby Chevy Chase –- just a few miles outside of Bethesda. Here, visitors can enjoy the scenery while walking on a wooded trail, or exploring wildlife in and around the pond.

The sanctuary is set on 40 acres, providing plenty of room to roam. Also on site is the historic Woodend Mansion, an early 20th-century estate that now houses the headquarters of the Audubon Naturalist Society and includes a collection of mounted birds and Audubon prints. As the winter holidays are approaching, the society hosts the annual Audubon Holiday Fair –- a great place to find gifts.

Bethesda Row Cinema

7235 Woodmont Avenue, Bethesda, Maryland 20814; Tel. 301.652.7273

One of the best things about big cities (or in this case the communities close to them) is access to foreign-language and independent films that don’t often find their way to smaller towns. The Bethesda Row Cinema, one of the newest additions to the Landmark Theatres family, is a prime example. Located in the center of the business district, the eight-screen movie house is dedicated to the tastes of the more discerning cinephile, offering the best in current international and independent movies. What’s more, the Bethesda Row Cinema has all the amenities that you’re likely to find at a big box venue (minus the Hollywood film line-up of course) like cushy seating, state-of-the-art sound systems, and large screens. The concession stand has the usual fare, in addition to a variety of coffee beverages and gourmet pastries.

Clara Barton National Historic Site

5801 Oxford Road, Glen Echo, Maryland 20812; Tel. 301.492.6245

At the Clara Barton Historical Site, the history of one of the most important not-for-profit organizations in the country is revealed, along with the story of the woman behind it all. As the founder of the American Red Cross, Clara Barton seldom separated herself from her life’s most important work and this turn-of-the-century home documents the vigilance and conviction with which she worked. Built in 1891, the mansion served as both the private residence of Ms. Barton, as well as the headquarters of the Red Cross.

In addition to her own personal belongings, the home was filled with medical supplies, blankets, and other necessities to support the work of the organization. During a guided tour, you’ll be able to catch a glimpse of 11 restored rooms that include Red Cross offices and Ms. Barton’s private quarters, as well as other areas.

Dennis and Phillip Ratner Museum

10001 Old Georgetown Road, Bethesda, Maryland 20814; Tel. 301.897.1518

Founded by two cousins bearing the same surname, the Dennis and Phillip Ratner Museum features visual arts with a religious theme. The museum’s collection consists primarily of works created by Phillip Ratner and includes paintings, sculptures, drawings, and graphic art that depict the stories and characters of the Hebrew Bible.

The Dennis and Phillip Ratner Museum also includes a gallery dedicated to children’s literature, where young ones are free to touch and explore. Since the Ratner Museum is open only a few hours per week, it’s best to call in advance and schedule a visit.

Glen Echo Park

7300 MacArthur Boulevard, Glen Echo, Maryland 20812; Tel. 301.320.2330 or 301.320.7757

There’s always something to do at Glen Echo Park. Recent renovations have made the historical landmark an ideal destination for both indoor and outdoor adventures. Outside, stroll around and enjoy the historic architecture, or go for a ride on the restored Dentzel Carousel – a treasure of the park for more than 80 years.

Kids will certainly have fun playing on the outdoor grounds, but there are also plenty of structured activities on-site geared especially toward young visitors like the Discovery Creek Children’s Museum where they can explore the arts and nature, and the Puppet Co. which features live productions. It’s worth noting that local dance enthusiasts are constantly raving about the Spanish Ballroom on the grounds of Glen Echo Park. Housed in a historic Mediterranean-style Art Deco building, the floor is large enough to fit well over 1500 people, and on most Friday nights, it’s open for all who dare to show off their ballroom moves as they listen to live music.

Grapeseed American Bistro and Wine Bar

4865 Cordell Avenue, Bethesda, Maryland 20814; Tel. 301.986.9592

At this local favorite, the vintage is essential, if not central to any visit. Known mostly for its robust wine list, the Grapeseed American Bistro and Wine Bar also has a delicious menu that is constantly evolving and continually inspired by the wines included in their offerings. Here, guests who are daunted by the task of trying to figure out what glass of white or red best suits their chosen entrée will be pleased to find that there’s no need for any guesswork. Each menu item is matched with the vintage that best compliments its flavor. It’s worth noting that many of the menu items can be ordered in small sizes, leaving you free to explore more options. Grapeseed American Bistro and Wine Bar also serve a large portion of their wines in sample sizes so you don’t have to commit to a full glass before you’ve found just the right taste to please your palette.

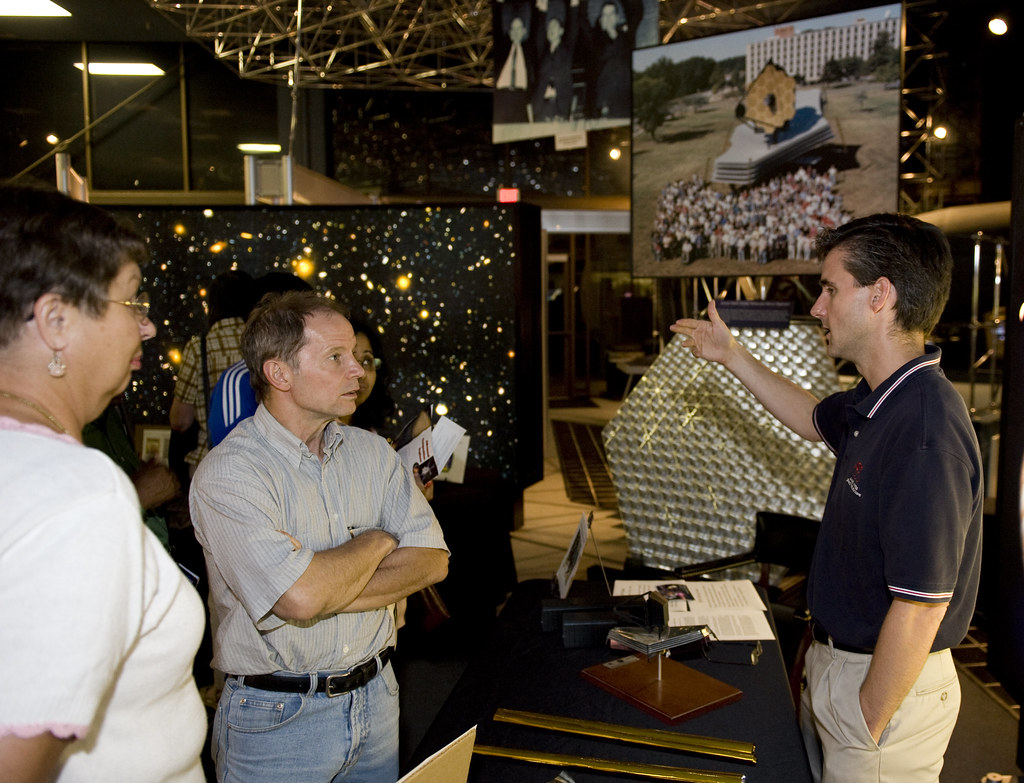

NASA Goddard Visitor Center

Code 130, Greenbelt, Maryland 20771; Tel. 301.286.9041

One of the best views of our galaxy and beyond can be seen at the NASA Goddard Visitor Center located just outside of Bethesda. Through exhibits dedicated to Earth, space, and technology, you can gain a new perspective on the universe by examining the center’s collection of photographs taken by the Hubble Space Telescope and satellites used to capture images of the atmosphere beyond our planet.

The NASA Goddard Visitor Center’s galleries also feature unique “Science as Art” exhibits and provide a historical perspective on the study of space and the technology used to help us understand it.

Round House Theatre

7501 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, Maryland 20814; Tel. 240.644.1099 or 240.644.1100

The relocation of the Round House Theatre has given this long-running performance troupe a new place to grow. Now in downtown Bethesda, the company’s recently established residence can fit twice as many people (approximately 400) and has all the amenities you’d expect to find at a modern theater. The company presents a diverse set of productions that encompass world premieres and inventive adaptations of popular classics from August Wilson to Anton Chekhov. If you’re around during the holidays, check out Round House Theatre’s fun-filled performance of A Broadway Christmas Carol – a favorite amongst local theater-goers.

Strathmore

10701 Rockville Pike, North Bethesda, Maryland 20852; Tel. 301.530.0540 or 301.581.5100

For more than 20 years, the Strathmore has provided local residents with cultural programming and events that include art exhibits, concerts, lectures, and much more. The center is housed in a historic Colonial Revival-style mansion and functions primarily as a premier venue for visual and performing arts. The Strathmore’s eclectic schedule that showcases everything from live jazz and classical music to visual art has something to suit every persuasion. During the summer months, visitors can enjoy the outdoors at the center while walking around and surveying the sculptures or lying in the grass and listening to a concert performance. Afternoon teas that take place at the mansion twice a week offer a unique experience and pleasant atmosphere enveloped by the soft sounds of piano, flute or Celtic harp.

White Flint

11301 Rockville Pike, North Bethesda, Maryland 20895; Tel. 301.231.7467

Known mostly for its upscale demographics, this popular mall goes simply by the name White Flint (no “mall” attached) and features three levels of shopping, dining, and entertainment. Anchor stores include Bloomingdale’s and Lord & Taylor, in addition to Borders superstore – a unique departure from the type of retail giants most often found at large complexes. Here, you’ll also find big (and popular) names in home goods and furnishings (think Pottery Barn and William Sonoma), as well as to the usual specialty shops and clothing outlets for men, women, and children. There’s also a small collection of local stores at White Flint. If you’re not in the mood for shopping, you can dine (and play) at Dave and Buster’s or catch a movie at the theater.

Bethesda Festivals

Bethesda Fine Arts Festival

May: Norfolk and Auburn Aves.; Tel. 301.215.6660

The Bethesda Fine Arts Festival features over 130 of the region’s best artists showcasing fine wares in their craft booths with daily live musical entertainment and food provided by some of Bethesda’s best restaurants.

Bethesda Literary Festival

April: Various Locations in downtown Bethesda; Tel. 301.215.6660

This annual Bethesda festival brings together novelists, journalists, poets and other writers at various bookshops around downtown Bethesda. The Bethesda Literary festival showcases essay contests, children’s workshops, poetry slams and author signings with question sessions.

Bethesda Row Arts Festival

October: Bethesda and Woodmont Ave.

Over 100 artists showcase their best talent at the Bethesda Row Arts Festival in an intimate setting where enthusiasts are encouraged to talk with the artist about their pieces and particular styles. The Bethesda Row Arts Festival is a wonderful opportunity to meet well-established artists and discover the emerging talent that the Bethesda Row Arts Festival always seems to bring.

Bethesda’s Winter Wonderland

December: Corner of Norfolk and Woodmont Ave.

The holiday season really kicks off in Bethesda with the Winter Wonderland festival that features ice sculpting and caroling with outdoor holiday concerts and storytelling. Also incorporated into Bethesda’s Winter Wonderland is the bi-monthly Bethesda Art Walk that showcases some of downtown’s top art galleries.

Imagination Bethesda Children’s Festival

June: Woodmont Ave. between Bethesda Ave. and Elm St.

A cultural and educational event designed specifically for children, the Imagination Bethesda Children’s Festival highlights the art of downtown Bethesda while making it accessible and fun for kids. Activities include craft tables, face painting, international dance performances, and theater performances all meant to expose kids to the culturally creative side of life.

Taste of Bethesda!

October: Norfolk, St. Elmo, Cordell, Del Ray, and Auburn Ave.

Literally, thousands of people reserve early October for the best regional festival in the Metro Washington DC area. The Taste of Bethesda Festival presents the opportunity for people to sample cuisine from over 50 of Bethesda’s world-class, and world-renowned, restaurants. Taste of Bethesda is simply one of the best food festivals because of the unique diversity of Bethesda’s restaurants that annually participate in the event. Also, there’s live musical entertainment and a kids’ corner where children can get in on the culinary escapades.

Featured Bethesda Restaurants

Bello Mondo

5151 Pooks Hill Rd., Bethesda MD 20814

A Bethesda dining staple for upscale diners, Bello Mondo serves contemporary Italian cuisine in an elegant setting. The signature dish, Cornia al Forno, or Baked Sea Bass, is a must. Bethesda’s Bello Mondo also has a full bar and a hefty wine selection.

Bistro Asiatique

4936 Fairmont Ave., Bethesda, MD 20814

Bistro Asiatique offers traditional French culinary art that meets the wonders of Asian cuisine. (Description provided by Opentable.com)

Cafe Europa

7820 Norfolk Ave., Bethesda, MD 20814

Europa consists of two separate parts; a cozy restaurant with homemade dishes, low-key atmosphere and friendly service; and an upscale martini lounge with live music, a martini menu, and daily happy hours. (Description provided by Opentable.com)

Centro Italian Grill

4838 Bethesda Ave., Bethesda, Maryland

Centro Italian Grill in downtown Bethesda serves contemporary Italian cuisine, heavy on Northern Italian influences with a dash of Californian cooking, in a chic setting that’s decidedly hip. The simple, yet extremely flavorful cuisine is all made using only the freshest ingredients and all of the pastas are made fresh every morning.

Daily Grill

One Bethesda Metro Center, Bethesda, MD 20814

The Daily Grill is a throwback to the classic American grills of yesteryear. The Daily Grill features huge portions of classic American food at a great value. (Description provided by Opentable.com)

Grapeseed

4865-C Cordell Ave., Bethesda, Maryland

Innovative in both cuisine and concept, Grapeseed Bistro in Bethesda makes its culinary mark by intimately and specifically pairing the finest wines with their always-fresh cuisine, both of which change daily. All plates are small so that the wine enthusiast can experience as many different pairings as their appetite will allow, but with so many masterfully done dishes, you’ll have to make many visits. Also, almost every member of the staff was trained at the local Bethesda culinary school—L’Academie De Cuisine—so you can be sure their technique, presentation and, most of all, the flavors they coerce from the fresh ingredients will be first-rate.

La Miche

7905 Norfolk Ave., Bethesda, Maryland

Country French cuisine reigns at La Miche in Bethesda innovatively remaining on the culinary edge while maintaining the traditional hominess of the French dishes that put it on the Bethesda dining map. The prix fixe menu of courses guides Bethesda diners through some of La Miche’s astounding country French dishes and is a great way to sample things you wouldn’t ordinarily try. Also, those in the know will dine at La Miche on Sunday evenings when bottles of wine are remarkably half-price.

Meritage Restaurant at Bethesda North Marriott

5701 Marinelli Road, North Bethesda, MD 20852

Located in the North Bethesda Marriott, Meritage offers excellent cuisine and elegant surroundings. (Description provided by Opentable.com)

Mon Ami Gabi

7239 Woodmont Ave., Bethesda MD 20814

Simple French fare is a study in potent minimalism and Mon Amu Gabi, with its elegant yet provincial atmosphere, serves excellent and satisfying French cuisine, sans pretension. Mon Ami Gabi also offers a varied selection of French wines.

Morton’s, The Steakhouse

7400 Wisconsin Avenue, One Bethesda Metro Center, Bethesda, MD 20814

Morton’s, The Steakhouse, the nation’s premier steakhouse group, specializes in classic, hearty fare, serving generous portions of USDA prime aged beef, as well as fresh fish, lobster, and chicken entrees. Morton’s is famous for its animated signature tableside menu presentation: steaks, whole Maine lobsters, and other main course selections, along with fresh vegetables, are presented on a cart rolled to your table, where the server displays and describes each menu item in appetizing and entertaining detail. The menu features a variety of favorite cuts, including a 24-ounce porterhouse, which is the house specialty; a 20-ounce New York sirloin and a 14-ounce double cut filet. Every Friday and Saturday night, enjoy slow-roasted Prime Rib. Morton’s Prime Rib is a double cut, served bone-in and roasted to a perfect medium rare. (Description provided by Opentable.com)

Old Homestead Steak House

7501 Wisconsin Ave., Suite 100, Bethesda, MD 20814

Famed New York based Old Homestead Steak House brings a reputation for excellence with adherence to quality to the third location of the boutique steakhouse in Bethesda, Maryland. Located in the Chevy Chase Bank Building at the intersection of Wisconsin Avenue and East-West Highway, the Old Homestead specializes in four major food groups: Beef!, Beef!, Beef! and Beef! Nationally acclaimed for Prime dry-aged steaks, the Old Homestead is also renowned for its whale-sized lobsters, salads, raw bar, seafood tower, and Kobe beef selections including Kobe burgers, steaks, and hot dogs! (Description provided by Opentable.com)

Persimmon

7003 Wisconsin Ave., Bethesda, MD 20815

Persimmon Restaurant features Modern American cuisine from Chef and owners Damian and Stephanie Salvatore. Located on Wisconsin Avenue in Bethesda, Persimmon has been in Washingtonian Magazine’s ‘Top 100’ list since 1999. Zagat Survey 2005 rates Persimmon as ‘Bethesda’s Best’, ‘creative’ and ‘charming’. (Description provided by Opentable.com)

Bethesda Hotel Guide

Four Points By Sheraton Bethesda

8400 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda MD 20814

Sheraton’s highly acclaimed mid-priced hotel chain offers an excellent opportunity to explore Bethesda, just outside of the bustle of the Beltway. This Bethesda hotel is located on the retail and dining-dense main stretch of the city, Wisconsin Avenue, and is minutes away from the sights and sounds of our cosmopolitan capital, Washington, D.C., accessible by car or public transit. Business travelers will be thrilled not only with the Four Points’ central location, but also with its large desks, two-line phone system, state-of-the-art business center, and, perhaps most importantly, a spa in which to relax after a heavy day of lobbying members of Congress.

Golden Tulip Bethesda Court Hotel

7740 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda MD 20814

This European-style Bethesda hotel offers quiet luxury and a full range of amenities for guests looking to take in the sites of the Washington, D.C. area. In addition to a full sauna and rich linens, the Golden Tulip has a doctor on call should one’s patriot fervor turn to fever. Visitors will want to check out nearby military-cultural landmarks such as the National Air and Space Administration, the White House and the National Zoo.

American Inn of Bethesda

8130 Wisconsin Ave, Bethesda MD 20814

This 76-room Bethesda hotel offers Old World charm in one of the strongest centers of New World power, Washington D.C. Located on bustling Wisconsin Avenue, the American Inn has received a praise-worthy 3-star rating in the Mobile travel guide. Attentive staff provides free parking, same-day valet services, and complimentary shuttles to both the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Naval Hospital. Each room comes equipped with free internet access and the hotel boasts an outdoor pool. Easy access to downtown D.C., Arlington National Cemetery and the plethora of monuments, statues, and points of interest.

Holiday Inn Select Bethesda, MD

8120 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda MD 20814

The Holiday Inn Select is a far cry from the motor lodges for which the chain first received cultural attention. This Bethesda hotel offers a truly expansive number of amenities, including a business center, secretarial service, rooftop pool and in-house gym. Employees are multi-lingual and are more than happy to help guests, both business and leisure, navigate the rich and rousing sites and civic institutions in the nearby Washington area.

Hyatt Regency Bethesda

One Bethesda Metro Center, Bethesda MD 20814

With a twelve-foot marble atrium, an on-site gym, a rooftop pool, and a grand Crystal ballroom, this Bethesda hotel is a travelerŐs dream. The beds are wide and covered in fine linen, and the bathtubs are deep and sturdy. The utmost in Bethesda hotel luxury, and minutes from Lockheed Martin, the NIH, Bethesda Naval Hospital, and downtown Washington, D.C.